The Makers of Canvey Island (part two)

By Mary L. Cox. 1902

Continuation of the article first published in the Home Counties Magazine 1902 including photos from the article.

Dutch Cottage, Canvey

Although the Dutch people gave to Canvey Island characteristics so familiar at the present day, not one of that community impressed the stamp of his personality upon the place and its institutions as did the actual “maker” of modern Canvey, the Rev. Henry Hayes. True it is the Dutch people, by their skill, made the island a comparatively safe dwelling-place from the inundations of the sea, but beyond that the only object they had was to find as satisfactory a return for their capital as possible. Mr. Hayes, from the first time he came on to the island, never ceased to make the welfare of the islanders one of the principal objects of his life. He first served the curacy from Leigh, for in those days there was no house available for the use of a clergyman. The little white-painted church with its red shutters and red-tiled roof was the chief landmark. Small farm-houses and cottages were visible at considerable distances one from the other; in the centre of the island an inn, of which the signboard portrayed a substantial red cow, with “A Bird” lettered below, intended to draw one’s attention, not to any freak of nature, but to the fact that the name of the worthy host was Abraham Bird; a second inn lying under the wall at Hole Haven; two inconsiderable clumps of trees (for Canvey is too windy to allow of much horticulture), and three tiny round Dutch cottages (one since blown down), built about eleven feet high and broad, with brick foundations and superstructure of mud, kept in position by a pargetting of cockle shells—such was Canvey when Mr. Hayes was appointed first vicar in 1872. These features still remain, but the island bears all the traces of a working, thoughtful energy. The church has been replaced by a larger building, with schools near by. Close at hand is a village with an imposing vicarage and picturesque thatched well, the boring of which was an expensive and lengthy undertaking, and, in the neighbourhood of the “Lobster Smack,” a trim row of coastguard cottages, which, together with the introduction of a post office, are some of the most apparent results of Mr. Hayes’ vicariate.

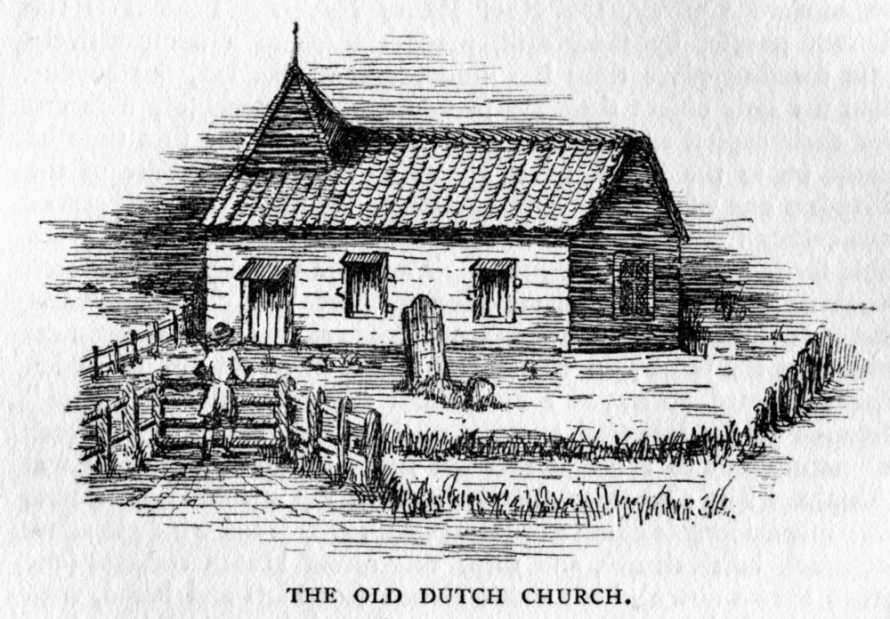

The little chapel found by Mr. Hayes was not the one left by the Dutch. After 1704 there seems to have been no regular worship. By 1712 the chapel had become so decayed that another was built at the charge of Mr. Edgar, an officer in the Victualling Office, who owned Chaffletts Farm, and consecrated on the 11th of June 1712, by Compton, Bishop of London, probably the first bishop to visit the island. He further settled £12 per annum on the same. This lasted some thirty years and more, when a new one was built about the year 1745, partly by a contribution of the inhabitants, but mostly by the benefaction of Daniel Scratton, esq., owner of considerable estates in Prittlewell. He also gave part of the tithes to trustees to pay £10 a year to the vicar of Prittlewell, the better to enable him to perform divine service there, and £10 a year more to the minister, or curate, duly appointed to preach twenty sermons in St. Katherine’s Chapel in the island. In 1768 about £17 a year was paid by the nine incumbents who took the tithes of the island. With this scanty provision the islanders had to content themselves for a long period, even to within the last thirty years.

Many of the islanders still remember this state of affairs, for said an old man in answer to an inquiry as to the services in the old church, “Well! he [the appointed clergyman] come a-Good Friday and never no more only twenty times as fast as he could and then we used to put up the flag.” This flag on the church was a quite necessary signal to the islanders when services did take place, as wind and weather would not always permit of the execution of clerical duties. For these auspicious occasions the shutters were taken down from the church windows and the smuggled goods removed from the sacred edifice, which, from its position, at a desirable distance between the shore and the mainland, was oftentimes made the depository of this class of traders. There were even times when it was intimated it would not be convenient for the clergyman to officiate on a particular day! A few years ago a small cavity was found in the churchyard near one of the present church walls, sufficiently large to store cigars or tobacco. Through all the winter months no services were ever held on the island. For marriage, the people were obliged, in many instances, to journey a considerable number of miles to the church of the parish to which their part of the island belonged; their dead they carried to the nearest churchyard, South Benfleet.

From the “Surveyor’s Rate Book, 1742-89,” many items of interest respecting the church expenses may be gathered. By 1761 the constant reglazing of the windows had become so great an expense that it was deemed expedient to make shutters. This necessitated an outlay of £2 is. 2d., with an additional expenditure of 9s. 6d. for painting. The clerks, for their services, received the sum of 6d every Sunday; the number of sermons, however, for which provision had been made, was seldom realized, and fell short by no less than eight in 1785. Only once in the season was the chapel cleaned, and with the early approach of autumn the sacred edifice was given over to loneliness and solitude, unless disturbed by the smugglers. This state of affairs practically continued until 1872.

With an indomitable energy, and wonderful capacity for enlisting the interest and sympathy of those with whom he came in contact, Mr. Hayes devoted himself to the development of the island, commanding the admiration and respect of all who knew him. One of his first acts was to secure the building of a school for the accommodation of some fifty children, for, owing to the improvements in the land drainage, brought about by the exertions and example of Mr. Danbury, it was possible for farm labourers to bring their young families on to the island without the risk of seeing the children fall victims to malaria, and until then no provision had been made for educating the children. The church clerk who, under the old regime, received 5s. per annum for his services, and who has been resident on the island for over eighty years, still remembers the days when only people who cared but little whether they lived or died would undertake the farm work on the island.

The building of the schools accomplished, Mr. Hayes turned his thoughts towards the enlargement of the church. As it then stood, dedicated to St. Katherine, it was a small wooden building accommodating some ninety worshippers, the interior remarkable only for the absence of pulpit and reading-desk, both removed to afford more space. The churchyard had but one tombstone, although only too well tenanted, for many have been the waifs of the sea cast upon the island’s shores, to find a last resting-place among strangers.

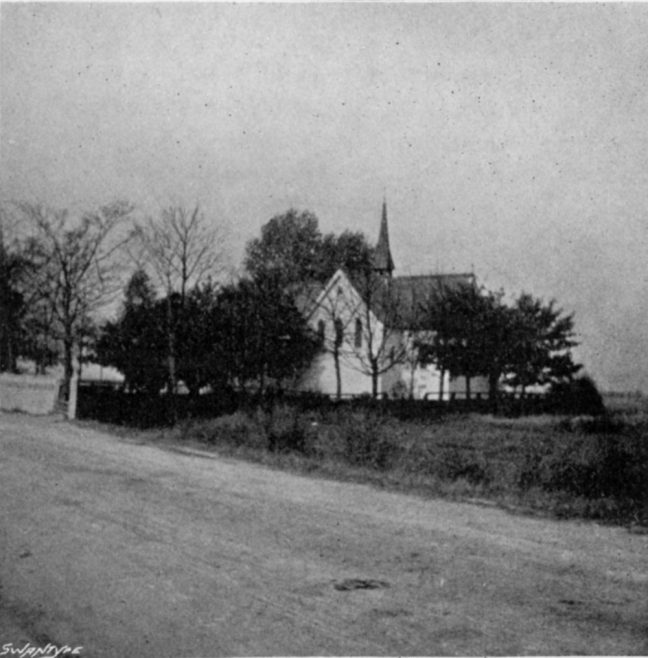

It was intended only to enlarge and re-roof this building, but owing to the difficulty of enlarging the site, it was rebuilt in the old churchyard about twenty feet further back from the road. The windows and porch of the old church were re-introduced into the new. This was consecrated November 9th, 1875, by the Bishop of Rochester. Three years later an organ, transferred from Great Waltham, added much to the little church.

Between the time of the active and persevering Dutch settlers, and the dawn of these brighter days, Canvey passed through many vicissitudes. During the ministry of the last Dutch pastors appointed to the community on the island, English interests were gradually again becoming predominant, and the number of English inhabitants greatly increased. Nevertheless, down to the year 1704 we may trace pretty accurately the activity of the settlement there. After this time the proceedings of the Dutch consistory of Canvey Island become somewhat obscure. That the conduct of affairs was hazardous and unhappy may be gleaned from a letter addressed from Canvey in April, 1705, by a certain Anna Ca[therina] van Rentzen, widow of Emilius van Cuilenborgh, to the consistory in London, in which letter she remarked that her husband (presumably the minister),” wounded to the soul by oppression, pain, and calumny, had at last yielded up the ghost.” He was buried in South Benfleet churchyard 13th October, 1704. Forwarding some of her husband’s MSS., she begs that the widow’s pension of £50, promised to her husband, should be increased by £10.

In the same letter she complains of the unhealthiness of the place, for then, even as for long afterwards, marsh fevers were the penalty of living on the island. The registers of South Benfleet record the burial of a Dutchman in 1623; three the next year, and in 1625 three more, and fourteen men, women, and children between that date and 1641. Then there is a gap of twenty years. Dutch names are of frequent occurrence in this register down to 1700. In 1710 there is an agreement between the overseers of the poor of the London Dutch Church and Jan Smagge, a farmer who rented thirty-eight acres of [marsh] land lately in the occupation of Peter van Bell, in the parish of North Benfleet, and in the south part of “Holy Head, alias Canvey Island,” at £8 per annum. In 1720 John Van de Voord, of Canvey Island, yeoman, leased this same ground for a term of eleven years at an annual rent of £12, with permission to plough up two small pieces of land, but no more, under penalty of £3 per acre.

In the same letter she complains of the unhealthiness of the place, for then, even as for long afterwards, marsh fevers were the penalty of living on the island. The registers of South Benfleet record the burial of a Dutchman in 1623; three the next year, and in 1625 three more, and fourteen men, women, and children between that date and 1641. Then there is a gap of twenty years. Dutch names are of frequent occurrence in this register down to 1700. In 1710 there is an agreement between the overseers of the poor of the London Dutch Church and Jan Smagge, a farmer who rented thirty-eight acres of [marsh] land lately in the occupation of Peter van Bell, in the parish of North Benfleet, and in the south part of “Holy Head, alias Canvey Island,” at £8 per annum. In 1720 John Van de Voord, of Canvey Island, yeoman, leased this same ground for a term of eleven years at an annual rent of £12, with permission to plough up two small pieces of land, but no more, under penalty of £3 per acre.

Respecting the property owned by the London Dutch Church on the island, a number of receipts furnish many items of interest. Thus, John Greenway gives a receipt, dated 5th September 1721, to Mr. Vanbord for ” Twelf Pound fifteen shillens by the order of the Dutch Church for 51 aekers at 5 shillen a naker for the ues of the seay walls.” About this time we find an entry, “If there comes an outrageous tide to allow in proportion what other gentlemen doe.”

Down to the year 1800, when Mr. Gardiner bought fifty-six acres from the deacons of the Dutch church in Austin Friars, many such accounts and business transactions show the close connection the Dutch community in London maintained with the island, although it is extremely doubtful whether any Hollanders had actually inhabited Canvey for many years prior to this date.

Property on the island has so frequently changed hands that it is often a difficult matter to trace the consecutive owners. Monks Wick is owned by the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul’s; in 1867 George Hilton, of Flemings Runwell, was lessee. It is in South Benfleet parish. Waterside Farm also belongs to the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul’s. About 1807, when in the tenure of Henry Wood, a fire consumed everything but the house. Being uninsured, his neighbours subscribed to make good the loss, and, to his honour be it said, he afterwards refunded all the money advanced. The Wood family, down to within recent years, has always held much land in Canvey Island. Their earliest known connection was in 1579, when Henry Wood rented Sharnard, in North Benfleet parish, and another marsh of Edmund Tyrell. He also owned Russells, and other marsh lands adjoining, purchased of Colonel W. Brewse Kersheman. Southwick Marsh, otherwise Tree Farm, formerly the property of the colonel, was purchased by Jonathan Wood, who also similarly acquired Little Brick House in North Benfleet and Prittlewell; it was afterwards acquired by William Kynaston, of Gresham Street, London.

Chaffletts and Fartherwicke were once the property of James Holbrook, of Tottenham, and afterwards of his sister, Mrs. Wakelin, of Tottenham. Afterwards these farms passed to the Wood family, then into the possession of Alfred and Charles Layard, and now are owned by Messrs. Arthur and George Clarke. In 1787 the house and buildings were consumed by fire.

Antletts, otherwise Antleach (called Brick House), and Sauldry Marshes, lying in Pitsea and South Benfleet, were owned by John Fell in 1749. Later Sir James Charles Dalbiac, K.C.B., bought this property, but resold it to Jonathan Wood. In 1860 it was sold by his trustees to Charles Asplin, of Tilbury, and has lately been acquired by the Kynock Company. Upon this farm is very prevalent the Lathyrus Tuberosus, a plant which it seems impossible to eradicate. The flower somewhat resembles the everlasting pea, with a bulb at the root, which is edible, and is said to have been introduced by the Dutch.

Rack Hall, alias Wreck Hall, alias Southchurch Marsh, in the parish of Southchurch, situate at the south-east side of the island (formerly consisting of forty acres), is all third-acre land. It was originally purchased by Ralph Robinson, of Horndon (circa 1770), for 100 guineas. This was resold in 1815 at the Bell Inn, Horndon-on-the-Hill, by William Jeffries, to the grandfather of Daniel Nash, who was owner in 1867, for £1,300. The family had made up their minds to let it go for £800, but the company being somewhat stimulated by sherry, and a competition springing up between Nash and Wilson, of Rochford Hall, the result was as above stated. When the purchase-money was paid at the Lion Inn, Rayleigh, to Jeffries and Charles Robinson, it was deposited in the boots of the recipients, for fear of footpads. The farm took the name of Wreck Hall from the circumstance that Ralph Robinson, purchasing of the underwriters the wreck of the Ajax (which was driven on shore opposite Burgess House at South Shoebury), employed the timbers in the construction of the premises. Knights Wick, situated in North Benfleet and Hadleigh, formerly the property of William Hilton, of Danbury, is now owned by Messrs. Arthur and George Clarke. Small Gains, in Hadleigh and Prittlewell, comprises what in old deeds is called Low Marsh, now better known as Sunken Marsh, and additional land bought of Richard Harrison, now in the possession of Mr. Foster.

Sluice Farm, partly in South Benfleet, is now owned by Charles Beckwith, the proprietor of the “Lobster Smack,” the chief of the two inns upon the island. This lies under the wall at Hole Haven, the house of call for unlicensed pilots, who are patronised by those captains objecting to the charges of the Gravesend pilots. There, in the evening, Dutch is frequently the only language spoken, for there the captains of the eel boats love to congregate and smoke their pipes. Germany is also represented, but not to the extent that Holland is, so that it frequently happens visitors might think they had been mysteriously transported to the home of canals and tall trees.

Respecting landowners past and present, the greatest possible interest attaches itself to the name of Henry Hayes, for with an interval of considerably over 230 years we find landowners in Canvey Island of that name. The parallel goes still farther, for the wives, in both instances, were similarly named. The original Henry Hayes, and Elizabeth his wife, lived on the island, acquiring a cottage, garden, etc., and died in 1657, leaving two sons, Thomas and Henry, and three daughters, Mary, Alice, and Elizabeth.

Whether the first Henry Hayes was in any way such a public benefactor as the second, it is impossible to say; no evidence goes to support such an idea. Nothing is more admirable than the work of the later representative of the name. Having achieved the rebuilding of the church and the establishment of the schools, he is to be found working for the erection of a suitable vicarage; later, the boring of the village well—one of the greatest boons to the island, as previously, with few exceptions, one was dependent upon the rain, or, worse still, ditch-water. In this respect many of the people were fastidious, only repairing for their supply to such ditches as were the homes of families of water-rats.

At Brick House there is a spring, but owing to the breaking of the sea-wall and consequent inundations, in January, 1881, it has become brackish.

The present Church, Canvey Island

These inundations still occasionally bring much damage and destruction to property, the most serious of recent years being the one above mentioned, when fifty acres were lost to the sea. Those who could do so left the island; the remainder took refuge in the higher rooms, awaiting, as they feared, the inevitable washing away of their homes. When the tide receded strenuous efforts were made to repair the breach in the walls. About four years ago there was again a disastrous break in the sea-wall on the north of the island. Dry and crumbling, owing to the lack of rain, it soaked up the salt water like a sponge, and three ominous cracks appeared. Through these the water gushed in torrents. The farmers hurried away with their wives and families, but the only lives lost were those of two bullocks. A strong north-westerly gale was blowing, and when it dropped the water rushed up in swollen volume, bringing destruction and desolation. After bursting the sea-wall the water followed the line of the dykes and ditches. One of the effects of this inundation may be seen in the skeleton trees of the photograph of Canvey Church, killed as they were by the sea-water.

Serious inundations, killing nearly all the cattle, occurred in 1731 and 1736, besides many of lesser degree.

Although Canvey remained until the last two years practically terra incognita, postal authorities nevertheless recognized the island under appellations such as would puzzle any but the officials of St. Martin’s-le-Grand; for instance:

Rev. mr hayes Canibell irland.

To the Vicar of the Parish Church of Convent or Canvy Highland.

The Vicker of Cordey ilient.

Such addresses are now far rarer than formerly, and most probably the days are not far distant when to mention Canvey Island will no longer elicit the question “Where is Canvey ? ” for it will be as well known as the neighbouring holiday resorts of Southend and Leigh.

Comments about this page

Thank you Janet.

Thanks for transcribing this amazingly researched local history I’d heard of ‘The Makers of Canvey Island’ but never had the opportunity to read it. I always thought Cracknell’s ‘History of a Marshland Community’ was the definitive history but it appears he must have gained most of the info from Mary. L.Cox’s research published 50 years previously.

Thank you. Very interesting. My greatgrandfather was Charles Asplin owner of Brick House etc and on his deathbed he advised his son – another Charles – to dispose of the property on the basis he would never be able to keep the sea out. This advice was followed and has gone down in family folk lore! As a child my mother – now 103 – would be taken to the island and loved to run along the sea wall to frighten the adults! Anthea Clarke

Add a comment about this page