Three Canvey Sailors Lost - A Naval Blunder? Part one

The sinking of HMS Aboukir, Hague and Cressy September 1914

In the early hours of 22 September 1914, about forty miles off the Hook of Holland; three Royal Navy cruisers H.M.S. Aboukir, H.M.S. Hogue and H.M.S. Cressy were torpedoed and sunk by a German Submarine. The submarine was Unterseeboot U9, under the command of Kapitanleutnant Otto Weddigen, who just a month before had married his childhood sweetheart. There were only 837 survivors and of the 1459 drowned (62 of which were officers) many were cadets and reservists. There was a public outcry at these losses and a court of inquiry was held. The senior officers of all three ships were censured.

Deemed by many sea going officers to have been avoidable, the incident eroded confidence in the government and damaged the reputation of the Royal Navy.

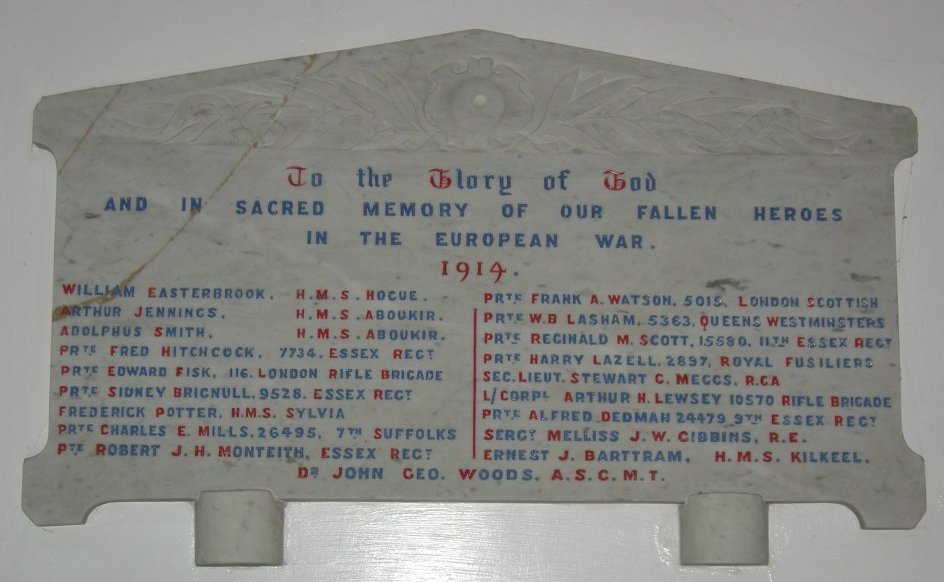

Memorial St Nicholas Church, Canvey

Three of the lives lost that day were:

Adolphus Smith (born 1886), a Leading Signalman aboard H.M.S. Aboukir. Died aged 27.

Arthur Jennings (born 22 Oct 1885), Stoker 1st Class also aboard H.M.S. Aboukir. Died aged 27.

William Thomas Easterbrook (born 22 March 1884), Able Seaman aboard H.M.S. Hogue. Died aged 30.

Their names are recorded on the 1914 Memorial in St Nicholas Church. The memorial is situated just inside the entrance of the church.

More about the men, their naval careers and their families can be read HERE.

___________________________

When World War 1 first broke out, the Royal Navy assigned a patrol of old Cressy class armoured cruisers to the south coast of England. These vessels formed part of a force of smaller destroyers and submarines stationed at Harwich. The job of this force was to block the eastern end of the English Channel and protect ships carrying supplies between Britain and France.

Due to rapid advancements in naval engineering leading up to the war, the Cressy class vessels were considered by many to be obsolete. They were designed for a speed of 21 knots but wear and tear meant they could only manage 12 knots, 15 at best. Manned for the most part by reserve sailors, their ships complements of 700 men plus officers were only brought up to full strength for manoeuvres or mobilisation. These nucleus crews were expected to keep the ships seaworthy the remainder of the time. In bad weather the destroyers could not sail, so the cruisers would often form the front line alone. They maintained a continuous patrol with some ships on station while others returned to harbour for refuelling of coal and renewing supplies.

There had been much opposition to this patrol from senior officers, including Admiral Jellico and Commodores Roger Keyes (commander of a submarine squadron stationed at Harwich) and Reginald Tyrwhitt (commander of a destroyer squadron also operating from Harwich). They considered the ships to be at risk of attack and sinking by modern German surface ships. In their opinion the ships were too old and the crews too inexperienced to put up a decent fight. Submarine threat was not considered a possibility. So great did they deem the cruisers vulnerability that the patrol was nicknamed the ‘Live-Bait Squadron’.

On 21 August Keyes wrote to his superior, Admiral Sir Arthur Leveson, warning him of the possible risks to these cruisers. By 17 September the note had reached the attention of Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. He met with Keyes and Tyrwhitt on 18 September whilst travelling to Scapa Flow to visit the Grand Fleet. In consultation with the First Sea Lord, Prince Louis of Battenberg, it was agreed that the cruisers should be withdrawn. A memo was drawn up stating:

“The Bacchantes (the lead ship) ought not to continue on this beat. The risk to such ships is not justified by any service they can render.”

Vice Admiral Frederick Sturdee, chief of the admiralty war staff, objected to this, stating that while the cruisers should be replaced, there were no modern ships available that could operate during bad weather. An agreement was therefore made between Battenberg and Sturdee to leave the cruisers on station until the arrival of the new Arethusa class light cruisers of which only one had been completed and the remaining seven were still under construction.

On 17 September four cruisers, H.M.S. Euryalus, H.M.S. Aboukir, H.M.S. Hogue and H.M.S. Cressy, continued their patrol without destroyer escort. Bad weather had forced the destroyers to return to port. The patrol was normally under the command of Rear Admiral Campbell aboard H.M.S. Bacchantes but in his absence the command fell to Rear Admiral Christian on H.M.S. Euryalus, which he undertook along with his other duties. By 6:00 a.m. on 20 September H.M.S. Euryalus had to drop out and return to port due to lack of coal and weather damage to her wireless. The weather was too bad for Christian to transfer to another ship so he passed command to the next senior officer, Captain John Drummond on H.M.S. Aboukir. He failed to inform Drummond that he would have authority to order the destroyers back to sea if the weather improved.

At 6:30 a.m. on the morning of 21 September the weather had calmed and the ships were patrolling at 10 knots (19 km/h), line abreast, two miles apart. Patrols were meant to maintain 12-13 knots and zigzag. These old cruisers though were unable to maintain such a speed and the zigzagging order was widely ignored as there had been no submarines sighted in that area. Lookouts were however posted for submarine periscopes or ships and one gun either side of each ship was manned.

U-9 Submarine

Early on 22 September 1914 the German submarine U9 sighted the Cressy, Aboukir and Hogue steaming NNE at 10 knots without zigzagging. U9 had a crew of 29 and was the most famous German submarine of the First World War. The U-boat’s commander, Kapitanleutnant Otto Weddigen, joined the German Navy in 1901 and became commander of a U-boat in 1911. Weddigen, had been ordered to attack British transport ships at Ostend, but had been forced to dive and shelter from the storm. He had passed by several British ships, including torpedo boats, as he was looking for “bigger game”. He could hardly believe his luck upon espying the “grey-black sides” of the cruisers “riding high over the water”.

The three cruisers formed a triangle and Weddigen could easily manoeuvre the U9 in to the centre, thereby enabling the submarine to strike any one of them.

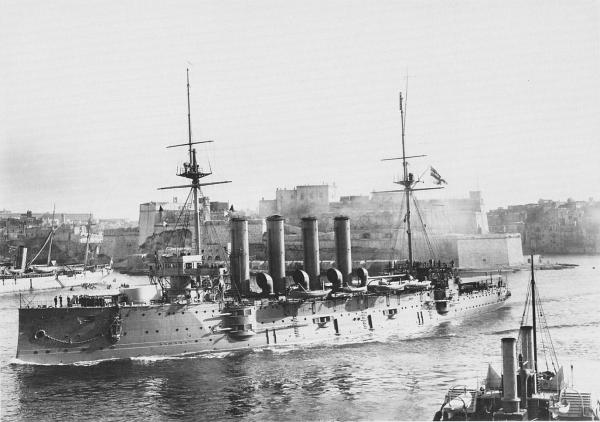

HMS Abaukir

At 6:25 a.m. the U9 fired a single torpedo at H.M.S. Aboukir from a range of 550 yards. This struck the cruiser on her starboard side, under one of her magazines which then exploded, hurling part of the vessel into the air. She suffered rapid heavy flooding and despite counter flooding developed a 20 degree list and engine power was lost. Captain Drummond assumed the Aboukir had struck a mine and so signalled the two other cruisers to close and assist. It was too late to order them away once he realised his mistake. When it became clear Aboukir could not be saved, Drummond ordered all hands to abandon her. Unfortunately only one boat had survived the attack so the crew were forced to jump into the sea. Less than half an hour after being attacked, the Aboukir capsized and sank. 557 men were lost.

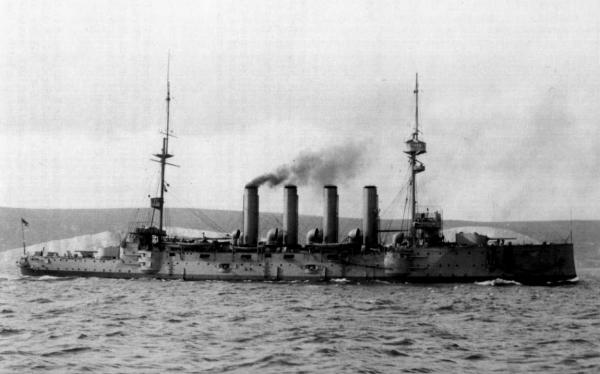

HMS Hogue

The U9 fired two torpedoes at H.M.S. Hogue. They hit her amidships and her engine room was rapidly flooded. Her Captain, Wilmot Nicholson, had stopped the ship to lower rescue boats to aid the crew of the Aboukir. He had thought the Hogue would be safe in its position on the other side of the stricken Aboukir. The U9 had unfortunately moved around the Aboukir. It attacked Hogue from a range of only 300 yards.

Having fired a second torpedo, mortally wounding the Hogue, the U9 was forced to surface for a brief time. It was fired upon by the Hogue but received little damage. It took less than 20 minutes for the Hogue to sink and the U9 turned its attentions on H.M.S. Cressy.

Weddigen described the men of the Cressy as being “brave and true to their country’s sea traditions”. The crew under Captain Johnson remained at their guns for as long as they could, searching the water for the U-boat and even attempting to run it down. Johnson ordered his crew to zigzag the Cressy as a defence, trying at the same time to assist the crews from the Aboukir and Hogue. The crew threw overboard all the loose timber on the Cressy to provide support for the men in the water.

HMS Cressy

At 7:20 a.m. the U9 fired two torpedoes at the Cressy from her stern torpedo tubes at a range of 1000 yards. One, of which the crew of the Cressy plainly saw the trail of as it approached them, struck on the starboard side. The other torpedo missed its target, so the submarine turned to face her one remaining bow torpedo towards Cressy. The remaining cruiser was listing but holding steady. The crew had already closed the watertight doors and scuttles when the U9 fired again at a range of 550 yards. This third torpedo proved fatal. It struck by the boiler room, which exploded. Within 25 minutes “in a cloud of dense black smoke” the Cressy rolled over to starboard and floated upside down until 7.55 a.m.

Distress calls had been received by Commodore Tyrwhitt, who with the destroyer squadron was already at sea returning to the cruisers with the improvement of the weather. At 8.30 a.m. 286 men were rescued from the scene by ‘Flora’ a Dutch steamship which had seen the sinking of the cruisers. A second steamer ‘Titan’ rescued another 147 men. More were picked up by two trawlers ‘JGC’ and ‘Coriander’, before the destroyers arrived at 10:45 a.m.

After the events of 22 September the remaining Cressy class ships were dispersed away from the British Isles and later disbanded. The reputation of the British Navy was badly shaken. It was hard to believe that such a thing could have been achieved with just one submarine. Admiral Christian was suspended on half pay for failing to make it clear to Drummond that he could summon the destroyers. He was later reinstated by Battenberg. Captain John Drummond was criticised for sailing in straight lines rather than zigzag and for not calling for destroyer support as soon as the weather improved. Rear Admiral Campbell was criticised for not being present and for a very poor performance at the inquiry at which he stated that he did not know what the purpose of his job was. The stopping of major ships in dangerous waters was banned and the order to steam at 13 knots and zigzag was re-emphasised.

Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen

Otto Weddigen returned to Germany as the first naval hero of the war. He received the Iron Cross, first class and his crew each received the Iron Cross, second class. Three weeks later on 15 October 1914, Weddigen, operating off Aberdeen, sank another British cruiser which failed to zigzag – H.M.S. Hawke.

________________________________

The story of the sinking has been told in a book called ‘Three before breakfast’ by Alan Coles

If you can add anything to this story, if you knew the men or have photos please contact us.

Comments about this page

Look forward to hearing about the Canvey people involved in this disaster

Coming very soon Dave

My Great-Uncle served on the vessel and was one who survived being attacked three times in one day. he was a bugle boy. He is mentioned in the book “Three Before Breakfast” Cecil Kneller was his name. I have a photo of him in uniform ( 1914 ) as well as a picture of him in his later years.

I have just found out about my great grandmother having 6 sons in the Royal Navy, she received a letter with a silver memento from the Privy Purse and also deepest gratification from the King. She lost her youngest son on the sinking of H.M.S Aboukir.

Add a comment about this page