The Dark Mirror, a word cycle (Canvey Island & Beyond)

by Bernard Durrant. Poet and Novelist.

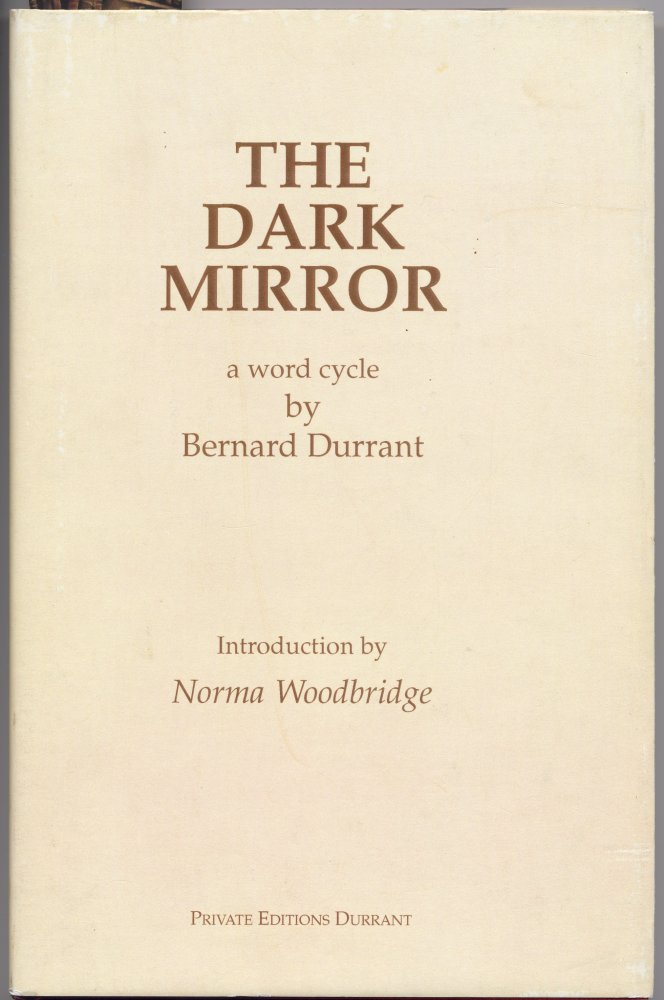

Bernard Durrant has given us permission to publish the part of his book that covers his time living on Canvey Island when he was a boy. Bernard is now in his nineties and still writing. The following is from the back cover of his book.

![]()

Bernard Durrant was born in Wimbledon in London and was educated at private schools. His early boyhood was spent on Canvey Island, a world unspoilt landscape in the Twenties and Thirties, a beautiful but ominous world of changing mood beyond the sea walls. The solitude of nature has haunted his imagination all his life, and much of his paintings and poetry reflect this loneliness of spirit. After the war he wrote travel scripts and broadcast for the BBC on various programmes. In 1968 he abandoned his ‘beachcombing days’ in Northern Australia and accepted the post as a college lecturer in Japan, a country he was to remain in for twenty years. Many of his poems take their inspiration from the disciplines of zen and the phyche afforded by such writers as Basho and Yasunari Kawabata. Ill health forced his return to Europe. He lives in Kent and enjoys walks along the clifftops facing the North Sea, not so far away from those waters of childhood around Canvey Island in that world of innocence gone forever.

![]()

Canvey Island & Beyond

Because of my weak chest and the London fogs, my parents moved to Canvey Island, on the Thames Estuary. It was wild, unspoilt place in the Twenties and Thirties; and from the start I could sense in the racing clouds sweeping over the brown-sailed coal barges the presence of a glorious authority, an awareness of light and colour that I could not hope to match with my crayons.

Suddenly revealed to me was all the sweet simplicity of nature herself, as I had never known her in Wimbledon Park. The tangy smell of the sea, the constant cries of gulls and terns were usually the last things I remembered before sleep.

And haunting too were my dreams when winter moon rode high over the island, as if my whole body was caught up in plaintive, sinister shapes of the sea mists reaching up to my bedroom window.

In those far off days Canvey was a real island, linked to the Essex mainland at Benfleet by a wooden, flat-bottomed ferry boat. On stormy evenings it was high adventure to make the ten-minute journey, huddled on the slippery deck, feeling that perhaps the end was near-my imagination was vivid; in truth we might be drifting towards Samoan breakers not ten cables’ lengths away from disaster.

Today, a hideous concrete bridge connects to the island; what dreams there are must be drowned in exhaust fumes.

Then however, the isolation was complete; beyond the sea wall roared the world and its tempests, until the spring came-sucking out the mud from under the duckboards in long drawn-out breaths of warm, fragrant sighs. Put back on the ceiling hooks were the hurricane lamps, their wicks trimmed, brasses polished; how gentle to the eyes they were in the dark caverns of winter, when all manner of beasts lurked in tumultuous parables at bedtime. That was the moment of the day, perhaps to be becalmed in nightmares as the estuary slept, when I would be afraid to close my eyes-in case the riding lights of stars keeling towards the east might shrivel me to death.

Memories are the only future we are denied.

And when I think of that home, I tell myself that my boyhood there could be what God meant when he made an island sing, weep, and sing again.

Although not yet twelve then, I had already found non-earthly worlds, unexplainable as in the heavens themselves – though not realising that the season was not too distant before I would set forth on a kind of inner journey; to seek a passage through uncharted seas towards a shore where lay – like gleaming stones in sunlight – enrichments of the heart’s intelligence.

Strangely, all through my childhood, I had always had the notion that I should seek for a sanctuary somewhere. At such a tender age, I did not realize I was seeking the impossible: stepping outside my own consciousness to somewhere autonomous, as in an Old Testament parable.

Now, I bow my head, a little ashamed, a little bewildered, as when something priceless eludes me which I would have loved to possess.

And my childhood is still calling out as I am scribbling this down, but I can hear the awful silence too: the past has overtaken me and gone racing on ahead, laughing back at me – the show-off thing!

![]()

Bernard Durrant has sent us a message about his Canvey memories, this can be read HERE

You can read more about Bernard Durrant’s life and works if you follow the link below

No Comments

Add a comment about this page