Canvey Island is not the first place you head for if you want to be awestruck. Awe certainly wasn’t the reaction that came to mind as I stumbled my way through the potholes and scrap-iron of the Charfleets industrial estate. Nor, do the letters BOPH set the heart on fire. Not at first sight, anyway. The BOPH workshop sits in just about the shabbiest corner of Charfleets. Here, however, I met Joan Lythgoe and her grand-daughter Joanne Blackwell, and things immediately started to lift up. Spend a couple of hours in their company and you emerge in such a state of elation that the Charfleets Industrial starts to look like Venice on a good day.

BOPH stands for Business Opportunities for the Physically Handicapped. Joan founded it and Joanne was the reason. Joanne has now been joined by 18 other good reasons. Any social-worker, local businessman or indeed journalist who encounters Joan Lythgoe is impressed by her qualities as a mover and shaker. She gets money, she gets buildings, she gets results. Her tenacity and energy are awesome. Yet there is no reason at all to doubt her when she says: “Until I became involved with BOPH, I was just an ordinary housewife and nan. I was that timid I wouldn’t have said boo to a goose.

Everybody who knew me is astonished by how I act now. My family still can’t quite believe that I could ever set anything up, because I always kept myself in the background.” Joan worked for a while as a supervisor at Standard Telephone and Cable in Basildon, but she had no training in social work, let alone executive action. “It was circumstances that brought out things in me that I would never have guessed were there,” she says, still sounding slightly surprised.

BOPH celebrated its second anniversary last month. It has now outgrown its premises in Charfleets, “a high-pressure headache, but a sign of our success I suppose,” says Joan. Its survival, let alone its growth, are nothing less than a triumph of the human spirit. That might sound corny, until you hear Joan Lythgoe’s story, recounted in matter-of-fact terms. She has fostered BOPH in the teeth of a series of hammer-blows that would have crushed a lesser fighter. Joanne, for who all this was started, is 20. She is pretty, vivacious and affectionate. She has also clearly inherited her grandmother’s ability to get what she wants.

Joanne’s sunniness in 1997 is in stark contrast to her dark and traumatic babyhood. At 10 months, her mother and father presented her for the standard infant inoculation. For millions of children, it is no more than a pinprick. For Joanne, a previously healthy child, it almost proved a killer. Reacting catastrophically, she went into a nine day coma. The first hammer-blow had struck.The second arrived in quick succession when Joanne was barely out of danger. It came in the form of an attack of meningitis. Yet Joanne survived even this. She was left with speech and learning impediments and partial paralysis, but was able to lead a normal and happy childhood.

Things changed when she left school. “You realise that everything is done for them during school-days. When they leave nobody wants to know, “says Joan. All that the world offered was a life as a couch potato, watching TV, mooching round the streets, paying the occasional visit to a day centre. Hence BOPH, which Joan and her husband Geoff founded in order to give a better future to Joanne and others like her — like Anne, for instance, who says “if it wasn’t for this place, I’d be wandering the streets today.”

With no training in social work or management the pair willed BOPH into being. They found BOPH’s current premises, corralled craftsmen to wire and furnish the workshop, fought for subsidies. Now social services departments from all over south-east Essex seek them out. BOPH was barely up and running when the next hammer blow struck. Geoff Lythgoe himself became ill and died soon afterward. Joan too has been seriously ill, but she drags herself on because “BOPH needs so much attention.”

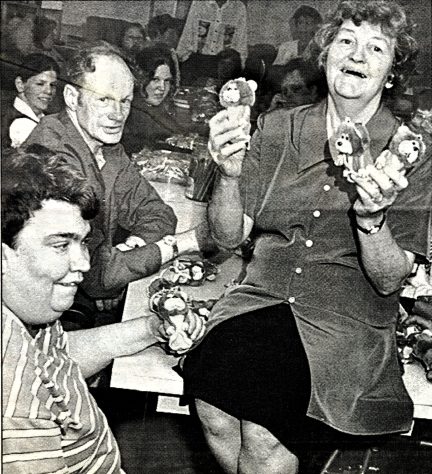

Yet nothing about the place suggests tragedy or loss. On the day I visited, the regulars were engaged on a variety of tasks — packing teddy-bears, cleaning computers for shipment to the third world, printing wedding invitations. The BOPH building was full of an unusual noise in workplaces — almost non-stop laughter. The effort Joan puts into BOPH is massive. When I finally met her in person, I found her energy being directed at a quite different quarter — self-effacement. Joan said: “BOPH isn’t Joan Lythgoe, it’s those who come here and work here who make it what it is. Talk to them.”

In deference to Joan, therefore, I talked to some of the regulars who come to BOPH. In the end, this proved just as good a way of getting to the heart of the lady herself and what she is all about.

Take Susan, for instance. She used to be petrified to leave the house. “I used to stay at home all day and watch TV. I never wanted to go out. This has changed my life. They can’t keep me home now. Joan is just brilliant.” Now Susan has mustered the courage to go up to London and watch her hero, David Essex. After the show, she was taken backstage to meet him. “It was brilliant, the best night of my life. I could never have managed that before I came here. I would have been too nervous.”

Then there is Michelle. She is a tiny, doe-like creature, who blinks at the light as if she has just emerged from a cave, as indeed, in a sense, she has. Much of her young life has been taken up “looking after mum, who had cancer and nowhere to go.” Now Michelle is free; but she has dyslexia, cannot read and write, and was so busy looking after her mother that she never had the chance to tackle these problems. “It’s hard to find a job if you’re like me. I wouldn’t know what to do or where to go if it wasn’t for Joan.”

Lucy is wheelchair-bound and Steve, who arrived at BOPH as a helper, has a stammer. This doesn’t prevent him from whispering sweet nothings to Lucy. They met at BOPH in June and on September 13 they will be married.

Individual success stories like these really are Joan Lythgoe’s life.

“BOPH occupies me for seven, no eight days a week,” she says. “It is constantly on my mind — who I can write to, where you can move to, can we take on somebody new, how we can make more money.

“I ask nothing for myself, but I’ve worn my knees out asking for things for BOPH.”

Comments about this page

My late brother Terry Stanley loved going to BOPH. He made many friends and thought Joan was the best.

Add a comment about this page