Canvey Island's Petrol Barge

Introduction

Between 1948 and 2003, a World War II Ferro-Concrete ‘Petrol Barge’ was a stand-out feature at Canvey Island.

As is well documented in the Press at the time, and on the website www.concretebarge.co.uk, created by local man Dave Bullock, on 22nd May 2003, the Canvey Island Petrol Barge was demolished by the Island Yacht Club. The purpose of this article is not to argue the rights and wrongs of that decision, but rather to position the Canvey Island Petrol Barge in factual, historic terms.

As is well documented in the Press at the time, and on the website www.concretebarge.co.uk, created by local man Dave Bullock, on 22nd May 2003, the Canvey Island Petrol Barge was demolished by the Island Yacht Club. The purpose of this article is not to argue the rights and wrongs of that decision, but rather to position the Canvey Island Petrol Barge in factual, historic terms.

After World War II, the Canvey Island Petrol Barge is said to have been laid up, along with other concrete barges, at Holehaven Creek, just off the River Thames. 200 of this specific type of Ferro-Concrete Barge (FCB) had been built between March 1943 and May 1944 by Wates at West India Dock as part of the ‘Overlord’ planning, to support the invasion by carrying fuel, approximately 185 tons per barge.

As I will explain, they were not actually used for ‘D-Day’ and so there were a lot of ‘war surplus’ barges being stored in a number of locations, most notably ‘Ham Pits’, off the Thames near Richmond, and around the River Medway. They were also to be found in large numbers on the Thames itself.

In 1948, the Petrol Barge was bought for £11 by the newly formed Canvey Island Canoe Club, intended for use as a floating clubhouse. A hole in the deck was opened and a hatchway built over it.

The Canvey Island Local Authority apparently wanted the barge moved immediately, according to accounts to be found on www.concretebarge.co.uk :-

“The barge was resting on the foot of the sea wall and could damage the wall, therefore we were to move it instantly if not quicker”.

On 31st January 1953, the ‘Great Flood’ turned the barge around, and moved it away from the seawall. The barge was ordered to be sunk by the authorities and so Canoe Club members hammered holes in the sides for this purpose. The Canoe Club disbanded in the mid 1950s and the barge was sold to Victor Vandersteen. It then changed hands again in 1980, sold for £1 to the Island Yacht Club.

In 2003, the barge was demolished causing something of an outcry. As to the issue of demolishing the barge, I will steer away from the rights or wrongs of this issue. FCBs of both Open Barge and Petrol Barge type have been demolished elsewhere, for example, at Brixham, Falmouth and Marchwood. They have been dumped variously in landfill sites such as Otterspool Promenade Extension on the River Mersey, at Whitehall Creek on the Medway, at Pomona Docks on the Manchester Ship Canal. They were scuttled in large numbers (around 40) in the Irish Sea by the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board, and in the Mersey Revetments off New Brighton.

How Many Survive ?

My research to date has located 187 FCBs still existent today in some form. 122 of these are Petrol Barges and 65 are Open Barges.

There were a total of 294 Open Barges and 201 Petrol Barges built during World War II so just over 60% of Petrol Barges ever built, still exist today.

This is a snapshot of the status of surviving Petrol Barges :-

55 are acting as Breakwaters, for example the 16 at Rainham Marshes, and 37 on the River Medway

17 are houseboats, some being as far afield as Amsterdam and Norway

38 are Jetties or moorings, most notably on the River Medway

4 are workshops / fisherman’s stores, for example one at Walton-on-the Naze

1 is an Office, ‘Brain of Brian’ at Penryn, Cornwall

5 are wrecks, one being in County Cork, Republic of Ireland

2 are floating in Hoo Sailing Barge Graveyard

So these Petrol Barges are not so rare, even 80 years on from when they were built. Open Barges are rarer, only just over one in five has survived, in any form.

The question that I am now going to answer is why so many Petrol Barges still exist today?

The Background – British World War II FCBS

The acronym FCB represents Ferro-Concrete Barge and there were two types of FCB. Open Barges, also referred to as ‘Lighters’ and ‘Dry Barges’, and Petrol Barges, also referred to sometimes as ‘Water Barges’ or ‘Tank Barges’. Open Barges were prefixed F.B. and the Petrol Barges were prefixed P.B. Both were suffixed with a number.

Open Barges

The 294 Open Barges were completed and launched between 26th October 1940 and 10th April 1945. They were prefixed ‘F.B’ and numbered in the range F.B. 1 to F.B. 300.

The reason that there were 294 is that 5 Open Barges, ordered to be built in Hull (F.B. 256 to F.B. 260), were cancelled and one Open Barge, ‘F.B. 82’, built in Barrow-in-Furness, was adapted to become the prototype Petrol Barge, ‘P.B. 1’.

Initially there were two designs and three builders of what were ‘Stem-Head’ Open Barges.. Wates at Barrow-in-Furness built their barges to Mouchel design, eventually building 137 Open Barges plus the prototype Petrol Barge, ‘P.B. 1’. Thomas Lowe & Sons built 13 Open Barges at Connah’s Quay and Gray’s Ferro Concrete Ltd built 9 Open Barges at Irvine, both to designs by Harry C Ritchie, a ferro-concrete engineer that had designed and built concrete barges in World War I. In World War II, all the Ferro-Concrete Barges were built using the methodology that Ritchie had pioneered, namely using pre-cast ribs and panels.

The Mouchel FCBs were 84’ long, 22’6” wide and 9’1” deep whereas the Ritchie designed barges were 81’9” long, 21’8” wide and 9’ deep. Following the construction of the first 40 FCBs, the Ministry of War Transport, in conjunction with the Admiralty, settled on the Mouchel design and they were built at Barrow-in-Furness during 1940 – 1942. In 1943, there was a significant acceleration in the FCB building programme with 100 FCBs being ordered to be built in London by Wates, and 40 ordered from Tarran Industries in Hull. Included in the order for 100 FCBs in London, in the range F.B. 121 to F.B. 220, were 50 ‘Swim-Head’ Open Barges, essentially to the same design as ‘Thames Lighters’, which were preferred by the ‘lighterman’ in London for operating on the Thames. The final Open Barge built was actually F.B. 255, built in Hull, and completed on 10th April 1945.

None of these Open Barges went to Normandy. They were for lighterage on inland waterways, rivers and dock use and built by the Ministry of War Transport and Admiralty, initially to provide additional barges at the West Coast Emergency Ports. For example, Liverpool were allocated 82 such barges, the Manchester Ship Canal received 32 and others went to Bristol, Swansea and Cardiff for example. The barges that did go to Normandy were the steel Thames lighters, converted in to all manner of ‘landing craft’ of which around 1,000 were requisitioned by the War Office during World War II

Petrol Barges

Petrol Barges were commissioned by the War Office in Spring 1943 as part of the ‘Overlord’ plan, with the specific intent of being used to transport fuel to support what became the D-Day invasion.

The prototype Petrol Barge, P.B. 1, ordered in December 1942,had been built by Wates at Barrow-in-Furness and engineered by Mouchel. P.B. 1 was accepted as the design for 200 further Petrol Barges, to be built by Wates at West India Docks, London, closer to the proposed embarkation points in the South East. Wates was able to construct 5 Petrol Barges per week in London, in addition to the 100 Open Barges also ordered around the same time.

From a design perspective, because the Petrol Barges were modelled on the Open Barges, they were exactly the same dimensions. They were built with four bulkheads in the hold, creating small buoyancy tanks fore and aft in the bow and stern, and with three large tanks capable of carry around 185 tons of fuel midships Their decks were constructed of relatively thin concrete panels, not designed to carry weight but rather to create a ‘lid’ to the tanks. There were five circular hatches above each tank and a rectangular hatch that gave access to the pump room.

They were built on the dockside in a row of 29 barges at a time and then craned into the water. A completed Petrol Barge weighed 160 tons, and because the Port of London ‘Mammoth’ floating crane had a limit of 150 tons, they were finished off once they had been launched and were floating.

By August 1943, according to ‘Overlord’ documents, 85 Petrol Barges had been completed and were berthed at Surrey Commercial Dock. By May 1944, 200 had been built in London.

Petrol Barges have nothing to do with Mulberry Harbours and they didn’t go to Normandy!

Ideas propagated on the Internet frequently include statements that FCBs went to Normandy and/or that they were part of the ‘Mulberry’ harbours. Neither are correct.

The only connections between Petrol Barges and ‘Mulberry’ is that they were built from ferro-concrete, that Wates also built Mulberry components and that they floated. They are barges – not breakwaters, pierheads, roadways or harbours. Even IF they had gone to Normandy, which they didn’t, they still wouldn’t be part of the Mulberry Harbours !

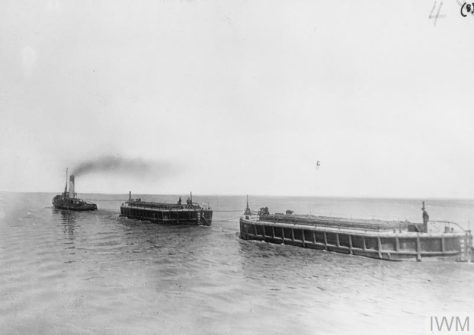

The possible source of the misunderstanding about their role, is that when the Mulberry harbour trials were undertaken at Garlieston, Scotland, in August and September 1943, a number of adapted Petrol Barges were, in fact, tested as possible pontoons to carry the ‘Whale’ roadway sections, adapted to support the Whale roadway sections.

There are photos of these adapted Petrol Barges at the Garlieston tests in the Imperial War Museum Archives. They actually show something of a ‘before and after’ due a significant storm. Allan Beckett, who was responsible for the Whale Roadways, explained in great detail in an Institute of Civil Engineering paper in 1949 why the tests on both Petrol Barges and Thames Lighters proved them to be unsatisfactory and why the ‘Beetle’ pontoons, designed and built for purpose, were selected. ‘Beetles’ were constructed in large numbers and indeed, more were built than were actually used which is why, for example, there are 39 of them in a row at Dibden Bay, Hampshire, acting as a coastal erosion defence.

Hopefully, this puts to bed the idea that the Petrol Barges were part of ‘Mulberry’.

Petrol Barges and the ‘Overlord’ plan

There is no question at all that the 201 Petrol Barges were built as part of the ‘Overlord’ planning, commonly known as ‘D-Day’. They were designed to carry 185 tons of fuel each so based on the theoretical maximum, that’s over 37,185 tons of fuel. Ultimately however, the 201 Petrol Barges were not used for the purpose for which they were built, and they did not go to Normandy.

There are a number of reasons for this. In July 1943, ‘Exercise Jantzen’, a beach landing trial, took place in South Wales and four Petrol Barges accompanied the landing force. Unfortunately, having been beached near Tenby, ‘P.B. 5’ broke her back and spewed petrol all over the beach, the incident being captured on film, again available in the Imperial War Museum archives. A sea trial in October 1943 resulted in one of the Petrol Barges sinking.

Records from the National Archives of the COTUG towing roster for D-Day specifically shows the Petrol Barges being excluded and they do not appear on the ‘TOP SECRET “BIGOT” schedule of Military Floating Plant & Equipment – Cross-Channel Movement & Tonnage Programme’ dated 17th May 1944.

Furthermore, from the point of conception in Spring 1943, numerous other options for providing fuel for the invasion emerged. Indeed, fuel was delivered by a variety of other means – ‘Jerrycans’, ‘Y’ Tankers, ‘CHANTS’, Landing Craft, for example. PLUTO – ‘PipeLine Underwater Transportation of Oil’ – started to deliver fuel by September 1944.

Bottom line, the concrete Petrol Barges failed their tests, they were not trusted and they were not needed. Hence, they didn’t go.

Not one single record of a ‘Mulberry Tug’ towing a Petrol Barge exists that I have been able to find. Not one single photograph of Petrol Barges being mustered for the Cross Channel journey exists, that I have been able to find. Not one single photograph of Petrol Barges at Mulberry A or Mulberry B exists, that I have been able to find. No one single wreck of a Petrol Barge has been identified at Normandy, that I have been able to find.

Conclusion, they did not go to Normandy !

What to do with 201 Petrol Barges ?

By the end of World War II, there were something approaching 200 surviving Petrol Barges, surplus to war requirements and taking up a great deal of space and occupying moorings in and around the Thames. Aerial views of the Thames in 1945 confirms this. There is, in fact, clear photographic evidence that, in 1945, large numbers of these barges were being stored in Ham Pits, a gravel pit off the Thames and also on the Medway. It would seem that a number were being stored at Holehaven Creek, although no photographic evidence has been found as yet.

One practical use that was conceived for the Petrol Barges was to use them to store water. ‘P.B. 8’, ‘P.B. 9’, ‘P.B. 147’ and ‘P.B. 167’ are specifically referred to in War Office records as ‘Water Barges’. I have found evidence of their use for ‘emergency water storage’ at many locations around the coast of Britain. In County Cork, Republic of Ireland, one was used as a water bowser at Bere Island.

By 1st July 1945, the Petrol Barges had been listed as ‘For Disposal’ and managed by the Ministry of War Transport, which became the Ministry of Transport in April 1946. A number were transferred to the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (19), a number were sold or donated to the Dutch Navy (16), but most were simply excess to requirements and were sold off, very cheaply ! Belfast Telegraph on 8th February 1946 reported that the Ministry of War Transport was offering 480 vessels, excess to requirements, for sale and that the Ministry’s catalogue comprised of ‘old and new ships of all kinds down to tugs and concrete barges’.

£11 is the figure reputed to have been paid by the Canvey Island Canoe Club, which is a little cheaper than £50, which seems to be the usual price point in 1948.

Large numbers were dispersed to the River Medway and research indicates that by 1953, tens were sunk in Ham Pits, a disused gravel pit off the Thames. The highest concentration of Petrol Barges that exist today are on the River Medway, used as the foundations for jetties, quays, coastal erosion defences and as houseboats.

The River Fal in Cornwall was also used as a place to store Petrol Barges that were, as late as the 1960s, subsequently dispersed to other ports and rivers around the country. The use that was made of them, initially, was to store water for emergencies but over time, they were resold and used as moorings, quays, jetties, coastal defences and also as houseboats, of which, as I have stated earlier, there are many find examples existing today.

The 16 Petrol Barges at Rainham Marshes and the Urban Myth that surrounds them

Undoubtedly, one of the best known collection of FCBs are 16 Petrol Barges clustered at Rainham Marshes, Essex. What is not in doubt is that 16 Petrol Barges were towed to Rainham Marshes between 1st and 3rd February 1953 as a rapid response flood defence during the ‘Great Flood’. They are still there now, 70 years later.

It is not uncommon for the Urban Myth about the 16 Petrol Barges at Rainham Marshes in Essex to extend to a statement they had been “towed back from Normandy” whilst throwing in a bit of Mulberry Harbour for good measure. You can read the Urban Myth on Wikipedia, and numerous other sites that have copied it.

The idea that they were towed back from Normandy is flawed, indeed bizarre, at so many levels, beyond the fact that they were never in Normandy ! In any scenario imaginable, it is utterly implausible that 16 Petrol Barges were simply hanging around somewhere in Normandy, nearly eight years after D-Day, and that tugs were sent across to France, in the midst of the flood crisis, to retrieve them and bring them back, seemingly in towable condition, despite the ravages of the preceding years.

Britain from Above provides an aerial view, taken on 3rd February 1953, that shows the Petrol Barges in situ at Rainham Marshes.

Interestingly, again using Britain from Above, I discovered a 1953 aerial view from Erith side of the river on 8th October 1953 that clearly depicts 26 concrete barges at Coldharbour, meaning that 10 were subsequently moved away. So 26, not 16, FCBs came from somewhere – somewhere very close by. Perhaps, Holehaven Creek or one of the other storage positions.

Summary

There is no question that the Canvey Island Petrol Barge is remembered fondly by many that knew her. As I stated at the outset, I am not arguing the rights or wrongs of her demolition, simply trying to put the barge in her factual, historic context.

So in a nutshell :-

She was one of 201 such concrete barges built in London with the specific purpose of carrying fuel to support the D-Day invasion

She was one of 201 such concrete barges that did not go to Normandy either as a fuel barges or as part of the Mulberry Harbours

She was one of a very large number of such concrete barges that were listed for disposal and were sold off cheaply as ‘war surplus’ from July 1945 onwards

Was she truly a historic vessel ? Well a number of FCBs are in fact listed on the Register of National Historic Ships, including the Open Barges on the banks of the River Severn at Purton, and a Petrol Barge named ‘Concretian’ at Lowestoft, but these are a very small fraction of those that survive today. Whilst there are many ‘survivors’, there isn’t actually a single Petrol Brage that is in a museum today, whereas F.B. 18, an Open Barge, is on display at the National Waterways Museum at Ellesmere Port.

I would say personally that she was an historic vessel, without being rare as such. Having developed a strange, rather eccentric, obsession with concrete ships, I believe that they are important as maritime relics, as Wartime relics and, from a ferro-concrete engineering point of view, in the development of pre-cast concrete. As Plato wrote in ‘Republic’, “Our need will be the real creator” and the ferro-concrete barges of World War II are surely prove that ‘Necessity is the mother of invention’ ?

I hope that this article has been interesting and has answered a few questions about the Canvey Island Petrol Barge. As a point of interest, there are two floating Petrol Barges in seemingly excellent condition at the Hoo Sailing Barge Graveyard (or at least, they were when I visited in December 2022)!

The remains of the Canvey Island Petrol Barge can still be detected at 51°31’08.22″ N 0°37 29.57″ E

Richard Lewis

May 2023

Sources and Credits

I have searched for, and found, huge numbers sources of information for the books that I am writing about British Concrete Ships of both World Wars. Below, for brevity, I am crediting primary sources that have allowed me to write this article about Canvey Island’s concrete barge :-

www.concretebarge.co.uk When Dave Bullock established this website around twenty years ago, he collected information from far and wide about not just the Canvey Island Petrol Barge, but also about many FCBs dotted around the country. His work inspired art, poetry and stimulated interest in the subject matter. As a researcher, author and speaker on this topic, I pay due homage to the prior works undertaken by Dave Bullock.

‘Reinforced Concrete Barges of World War II – A Working Paper’ 2nd Edition by Philip Simons, published by the World Ship Society, 2012

Britain from Above & Google Earth Pro – for aerial photographs and satellite imagery

The National Archives – and in particular :-

WO 107/149 : ‘Overlord”: Tugs, lighters and concrete petrol barges :- Concrete Petrol Barges’.

MT82/97 : ‘Ancillary Craft and Specialised Equipment : Concrete Tank Barges : Proposed Use of Mylor Yacht Harbour’.

MT9/3384 : ‘Shipbuilding and Repairs (Code 114): Shipbuilding:- Construction of Concrete Barges’

MT15/1403 : ‘Proposed 90’ ferro-concrete barges for service on River Severn between Cardiff and Stourport.’

ADM 1/13179 : ‘Berths for Concrete Barges under Construction for the Army’

www.hamiswheretheheartis.com

British Newspaper Archives

Imperial War Museum

Concrete Shipbuilding 1848 – 1972 – Erlend Bonderud (as yet unpublished)

About the Author – Richard Lewis

I developed a strange, rather eccentric, obsession with concrete ships from 2019 onwards. I can’t really explain why they fascinate me, they just do.

I have written many published articles on the subject and was proud to be published in the Cumbrian Industrial Society’s collection of papers, ‘The Cumbrian Industrialist’ Volume 13, in April this year. I also wrote the history of concrete ships for the Irish National Maritime Museum and have been published variously on the internet, the references for which are on my website at https://thecretefleet.com/about-us-1

As regards my website, I try to keep refreshed with new, interesting information about concrete ships that I discover from my research. I am now ‘Blogging’ and soon ‘Vlogging’ about the topic. I use Facebook, Instagram and more recently Twitter to try to generate interest in the subject matter. Maybe one day, I will have a published book !

Further information, including the World War I concrete ships, may be found on www.thecretefleet.com and on my Facebook page @thecretefleet.

At present, I am on a mission to have Wikipedia, and many other websites, expunged of the nonsense that is written about the World War II British Ferro-Concrete Barges.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page