The East Coast Floods of '53

Written by Helen Rees (nee Tremain)

At the Book Festival for Alan Whitcomb’s book ‘Hops, Floods and Doodlebugs’ at Canvey Library on Sun March 21st I met Helen Rees (nee Tremain) who showed me this article she had written and had published in the ‘Eaglet’, the M.E.N.S.A magazine. She asked if the Archive would like to publish it too. Naturally, we are only to pleased to do so.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I was ten and living on Canvey Island in 1953. The year was not, for me, memorable so much for the Coronation of Elizabeth II, or the conquest of Everest as it was to many others, but for the floods that came at the end of January. I awoke on a Sunday morning to hear voices discussing how Irene, a neighbour’s child, would be better upstairs. I sleepily teetered out of the bedroom wondering vaguely what all the white stuff was outside, glancing quickly it looked like snow, but actually it was water. When I walked, still sleepy, into the living room it was full of people. It seemed they had been on their way home from a dance in the early hours of the morning, when with water rising, they had seen lights on in our house and sought refuge there as they knew my father. It was an odd sight to see them all at seven in the morning sitting drinking tea in full evening dress.

The Tremain’s family home,(cnr Leigh Rd / Ferndale Crescent.)

Evidently someone had phoned Dad, (I found out later the message had come via my future in laws who had a taxi business and so chatted to the telephone operator) to tell him of the danger of flooding as a surge tide swept down the East Coast. He had gone to the shop we had in the centre of town to move stuff off the floor, but unfortunately that shop did not get flooded though others did.

All morning Mum fussed about starting and stopping cooking Sunday dinner. Somehow Grandma and Granddad arrived from their bungalow – the water was under their floorboards but people living close to them had been badly flooded. They had put all their chickens in the loft rooms and scattered food, and as it turned out the chickens were to be there for a month – and survived. Dad decided it would be best if he took Mum, John and me to friends in Benfleet – so the dinner was left for Grandma and Granddad to eat while we slowly drove off the Island, apart from stalling once or twice in the water, when Dad had to push and Mum steer which scared John half to death. However we arrived safely at Benfleet and stayed with another ‘newsagent’ family – the Grants. In the afternoon we went to Doris Grant’s mother’s house at the top of Benfleet Downs and watched the straggly line of people managing to walk along the Winter Gardens footpath off the Island carrying as much as they could. In the late afternoon Dad returned to our house on Canvey hoping to sit out the flood there with Grandma and Granddad.

Long Rd under water.

The next morning, because Fenchurch Street – Southend railway line, had been flooded, the newspapers were arriving at different times and Doris, who usually did the early stint in the shop, asked her husband (who had had heart problems) to come and give a hand getting the newspaper rounds out. Sadly he had another heart attack in the shop, came home and went to bed to rest. A little later, when Doris’ Mum took him a cup of tea up, she found he had died.

I tried that morning to be completely absorbed in my hobby of sticking stamps in my album, but was actually listening to the procession of people coming to see Doris (who held herself responsible for Jerry’s death) offering sympathy and help. At lunch time, to everyone’s relief, Dad arrived having decided with no electricity, gas or water (apart from seawater) that it was wise to get off the island, though as the water had continued rising as the seawall was badly breached he had to use the dinghy in the garage next door to enable him, Granddad and Grandma to get off. However, not one to give up on his work of distributing the news, he went on to the Island every day for the month we were living off it, to distribute newspapers to the soldiers who were rebuilding the walls. Doris was much relieved to see Dad and he took over the running of her shops for the time we were ‘evacuees’.

It was then decided it would be better if we children were taken to stay with Mum’s brother Uncle Laurie and his family, but as John refused to leave Mum, I was taken alone to Chingford to stay with Uncle Laurie. After a week of utter boredom while my cousins were at school I practically begged to be allowed to go to a local school. Thus the following Monday morning Auntie Lily took me to meet the headmaster of Hazel (my cousin’s) school. I was in the final year of the junior school about to take the scholarship (as the 11+ was called then). He asked me if I thought I should be in an ‘A’ or ‘B’ class. Although at home I was in the ‘A’ class, I have never found it easy to blow my own trumpet and said I did not know. When he asked whether I would prefer a man or a woman teacher, much to his and my Aunt’s amusement, I replied immediately ‘oh a man’ and so I was put into Mr Shepherd’s class. As we had only brought my best Sunday clothes off the island I had to wear them for school and that coupled with the floods being national news made me as ‘an evacuee’ feel rather important. After being at the school for a couple of days my sense of importance increased when I was hauled up in front of the class to give an account of the, as I saw it, ‘adventure’ (although for my parents this must have been a worrying time as even though the house had not been flooded they did not know whether their business would recover and thrive again).

At this time Cinema clubs were popular, cheap events on a Saturday for children all over the country. My older cousin, Bernard, felt very important when he took me to the manager at the cinema nearby introducing me as a poor evacuee from the floods and asked that I be allowed to the sessions without being a permanent ‘club member’. The sessions usually had a set format – a couple of cartoons, the main feature often a cowboy film which was always accompanied by much whistling and shouting (I always stuck up for the ‘Red Indians’) and then the serial, often that was the equivalent for the time of Star Trek.

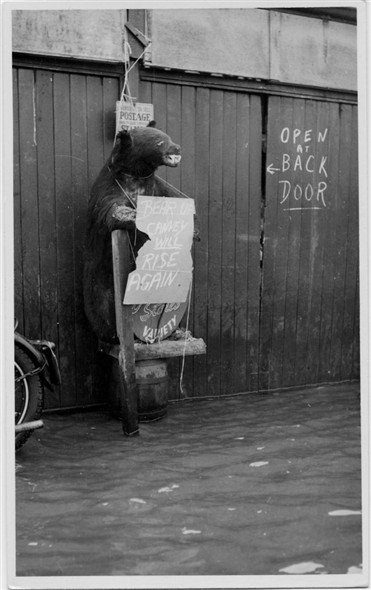

Albert Jones’s Bear; ‘ Bear up Canvey will rise again’.

Mum and Dad visited me each Sunday and after a month announced we could all return to Canvey. Emergency work on the sea wall was complete but now the serious task of strengthening it and increasing it began. At first only about half the children came back to school. Some families had lost a member in the floods and did not want to return to Canvey, others whose houses had been badly flooded had to wait until their houses were dried out and made habitable again.

The floods had been world news and gifts for the people of Canvey were sent from all over the world but particularly from the people of Canada. W.V.S. shops were set up to dish out blankets and the like. Every household on the Island received a carpet delivered from the Canadian government. At school there was Pepsi to drink instead of milk which, although I did not like Pepsi, it was good for me as it meant there were always spare milks to enjoy at the morning break. We all got a parcel of toys, and, because the effects of salt water on the soil had to be reversed, everyone could collect bags of Gypsum to put on the ground. For the farmers who still existed on the Island it must have been a massive task. The Red Cow pub that had housed the soldiers doing the emergency work was renamed the King Canute. Barclays built a new bank to show their confidence in the survival of Canvey as a residential town rather than the holiday place it had been and the stuffed bear outside Jones’ general store had a placard round its neck with the words ‘Canvey will bear up again’. In June we eventually took our scholarship (11+) and apart from ongoing work on the seawall for months and months, life returned to normal.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page